|

The following article was published in

California Living in 1979.

The piece was an historic first for llamas in that it was the first time a llama

was known to be monitored by a national park, at a time when there was strong

sentiment and ridicule against llamas. Sunny's performance and the success of

animals that followed him resulted in allowing llamas into Sequoia Kings Canyon

National Park and their eventual inclusion into the park's backcountry

management plan. The following article was published in

California Living in 1979.

The piece was an historic first for llamas in that it was the first time a llama

was known to be monitored by a national park, at a time when there was strong

sentiment and ridicule against llamas. Sunny's performance and the success of

animals that followed him resulted in allowing llamas into Sequoia Kings Canyon

National Park and their eventual inclusion into the park's backcountry

management plan.

The man approaching on the trail

stopped and frantically adjusted his camera. Peering through the viewer, he

commanded, "You guys are too ugly. Get out of the picture. I want that

beautiful llama." The shutter clicked. "Got it. Did you guys start in

the Andes or am I lost?"

"Neither," I answered. "Sunny is the

first pack llama in Sequoia Park."

"Where you guys headed?"

"We're going to climb Mount Whitney

tomorrow."

"Can a llama make it up Whitney? It's a rough

trail and awfully high."

"I hope he makes it. That's what we're here to

find out."

After a few chuckles and an exchange on trail conditions and the weather, we

bade our good humored fellow backpacker farewell and continued on to Crabtree

meadow.

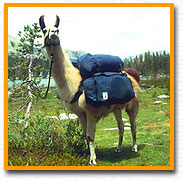

Rolland and Bill - two fourth-year veterinarian students, Sunny and I were

on the fourth day of a 100-mile trek which would take us across the Sierras and

back again, while climbing the highest peak in the continental United States,

14,496 feet. To be sure, the undertaking was quite an experiment. I had trained

Sunny, who learned quickly, to take commands and carry a pack. Sunny and I had

jogged three miles every day for two months prior to the trip to ensure top

conditioning for both of us. The Park Service had granted a permit and asked me

to take careful notes on Sunny's habits throughout the trip. I knew that llamas

would have less impact than conventional pack animals. They eat about one

quarter as much as a horse and have padded feet instead of hefty hooves that dig

up meadows.

I believed Sunny would do fine but there were unanswered questions. Llamas in

the United States have been a static gene pool since Federal law prohibited

their importation in the 1930s. Although Sunny's ancestors lived at elevations

of 15,000 feet in Peru and have been used as pack animals for 2,000 years,

several generations had been born in the United States. Would he be able to

handle the altitude? Would he be able to deal with the intense heat of the

southern Sierra? Sunny had packed before, but never more than twenty miles. How

would he perform on a seemingly endless journey over every conceivable kind of

terrain; sharp rocks, snow, swift streams, and loose shale?

The first morning in the Mineral King parking lot was spent dividing up gear

and food. Sunny was assigned sixty pounds and the three of us started with about

thirty pounds. We had provisions to last ten days. We got a late start and

faced a dehydrating seven mile 2,850-foot climb to Farewell Gap in an

exposed sparsely wooded valley.

As we started out, we passed a large pack outfit. A couple of hands sat on

the corral fence in full western garb. I waved and they stared. Park officials

had told us that some packers had objected to our going into the park because

llamas might scare their stock. Sunny and the mules in the stock pen looked each

other over. It occurred to me that llamas and the cowboy mystique might be more

incompatible than llamas and mules. A fully decked-out wrangler just wouldn't

look right leading a llama through the mountains. He probably wouldn't feel

right either.

Soon we started climbing through green meadows decorated with red Indian

paint brushes , blue lupins, red granite outcroppings, and a few old fir

trees. The peace and beauty quickly overcame the anxiety I'd felt in the

weeks of planning, talking to park officials, and training Sunny. As we climbed,

the grass gave way to rock. The plentiful marmots added a comical touch.

They popped up and down scurrying this way and that as if our presence were big

news in the marmot community. Suddenly a doe appeared on the scene. She kept her

oversized ears turned attentively to us and kept sniffing the air as she

approached. It seemed the doe was curious enough about Sunny to forget about us.

Eventually she came to her senses and bounded off down the slope. Soon we started climbing through green meadows decorated with red Indian

paint brushes , blue lupins, red granite outcroppings, and a few old fir

trees. The peace and beauty quickly overcame the anxiety I'd felt in the

weeks of planning, talking to park officials, and training Sunny. As we climbed,

the grass gave way to rock. The plentiful marmots added a comical touch.

They popped up and down scurrying this way and that as if our presence were big

news in the marmot community. Suddenly a doe appeared on the scene. She kept her

oversized ears turned attentively to us and kept sniffing the air as she

approached. It seemed the doe was curious enough about Sunny to forget about us.

Eventually she came to her senses and bounded off down the slope.

The heat was intense as we marched on. Llamas sweat through their padded

feet, so it wasn't long until Sunny showed an eagerness to go wading in every

stream we crossed.

Rolland and Bill run in two or three marathons a year. Needless to say, they

hiked at a fast clip. Sunny kept pace. About six miles into the climb, Sunny

surprised me by lying down and refusing to get up. He had never done this

before, so at first I was concerned. We checked him and saw no signs of

overheating or rapid breathing. It appeared he was simply balking, so after some

intensive badgering we forced him up. I decided I'd give him a rest when it

seemed appropriate and that way I'd be in command. If he were allowed to pick

resting spots and the frequency of rests, he'd be training us.

After reaching Farewell Gap, we traversed a snowfield which Sunny enjoyed

-

most likely because of the cooling effect on his feet. After traveling

about a mile down some switchbacks, we made camp next to a beautiful stream in a

meadow. Sunny was tied to a small log he could drag about as he grazed. We dined

on macaroni while Sunny munched wild onions and alpine grasses.

Bill was impressed with Sunny's intelligence, "Have you noticed Sunny

never gets tangled in his rope? When the rope gets wrapped around his leg he

methodically works it loose. He doesn't panic."

The next day, chiefly because of an elaborate breakfast ritual my two

companions had developed on previous outings, we broke camp at ten o' clock. It

was already sweltering and the day's journey called for a southern exposure on

sparsely wooded slopes, a drop in elevation, a steep 1,500-foot climb to Coyote

Pass, and a drop of 4,000 feet into the Kern Canyon - all of which would

encompass some sixteen miles. The landscape was desert like; sandy soil with

little ground vegetation and little water. There were some outstanding granite

formations that looked like they belonged in the backdrop of a Hollywood

western. Despite the heat, which bothered all of us, Sunny did well. By evening

we reached the Kern River ranger's cabin. Bruce, the ranger, had just returned

by horseback and gave us a warm welcome. He moved his mules to give Sunny his

best pasture, showed us a beautiful campsite and invited us to his campfire for

a glass of wine after we made camp.

Around the fire Bruce told us there was a serious bear problem in the Kern

River Canyon this year. As much as Bruce hated it, he had to find the bear and

mark it so the animal could either be destroyed or moved, depending on its

record.

The next morning the breakfast ritual put us on the trail at 10:30 with the

temperature near ninety degrees. We came across Bruce's mules and one of them

ran around braying. Apparently, Sunny's unfamiliar form bothered him. Sunny drew

behind me for protection and stared intently at the spectacle.

The heat was stifling, but just seeing the rushing Kern River made it

bearable. There would be little climbing during the twenty miles in the Canyon.

We traveled through shady hot stretches into lush fern areas that were heavily

wooded with cottonwood-fern groves. I was startled by the electrifying buzz of a

rattlesnake coiled about five feet to my right. After the initial heart flutter

I focused on the sinister looking head that was cocked and ready to strike.

Sunny was curious and acted as if he'd like to investigate by sniffing. Llamas have little knowledge of snakes. I carefully led Sunny around our venomous

friend and within ten minutes faced another rattler. This one was intent on

holding his ground. He lay directly on the trail sunning himself and instead of

coiling he merely raised his head and tail and gave the warning to stay clear.

From then on I kept my eyes riveted on the trail ahead. In less than half an

hour another rattler slithered between some rocks and sounded his warning.

Despite the snakes, the day proved enjoyable with the cooling ferns and

cottonwood groves. We encountered deer, a colorfully plumed Western Tanager and

large grouse. We marveled at a freshly cut cottonwood that a beaver felled

across a stream. A logger couldn't have placed it better. We even came across a

couple skinny-dipping in a large pool. By late afternoon we reached Kern Hot

Springs. The soaking pool, big enough for two, was close to the river. After a twenty-minute

soak, a plunge into the icy waters of the Kern came close to being a spiritual

experience. We soaked and plunged while Sunny grazed and rested.

The springs were relaxing but a note of warning attached to a nearby tree

explained what night might bring.

"Backpackers: Hang your food with care. A very smart, very persistent

bear who understands the relationship between anchor ropes and hanging food

stops nightly. Be careful."

The note persuaded us to camp away from the Springs. The mosquitoes were so

annoying that Sunny came close to the fire in his nervous pacing. He sat about

three feet from the flames. The smoke drifted about his head. We moved him but

he went back and sat in the smoke again. He had discovered a good mosquito

repellant.

We hung our food with care and tied Sunny close to my sleeping bag. In the

morning we found the night's only intruder was a very small mouse who had gnawed

his way through the poncho in my pack.

Because we had grown tired of traveling in the heat of the day, and because I

had grown tired of late starts, we decided to try a new approach. We broke camp

at 5:30 a.m. We planned to hike until noon, take a three-hour siesta in the heat

of the day, and continue when it cooled some. Hiking in the early morning gave us

all a lift. Sunny traveled lightly with his head constantly swiveling like a

sightseer in a foreign land. Sunny's quiet ways often allowed us to see wildlife

before it saw us. By nightfall we covered eighteen miles and found ourselves

2,500 feet above the Kern on the John Muir Trail.

The next day we headed south on the Trail and found out why many backpackers

consider it a highway. We ran into people about every half hour. There was some

good comedy in watching them clamor and fumble for their cameras upon seeing

Sunny. By noon we reached Crabtree Meadow, which was nine miles and more than

4,000 feet below the summit of Mount Whitney. We spent the afternoon playing

hide and seek with some curious marmots. We also found iridescent golden trout

in the pools along Whitney Creek. That night as I lay in my sleeping bag looking

at Mount Whitney I already knew the outcome of tomorrow's climb. Sunny would

make it and unknowingly commit his kind to years of packing in North America.

Since we were on the west side of Whitney we could hike in the shade for a

great deal of the time the next day, which would be a great advantage

considering there wasn't much water above 12,000 feet. By 6 a.m. Sunny was

loaded with about fifty pounds and we were off. The tops of Mount Whitney and

Mount Russell to the north were pink from the early morning light. Sunny and I

had worked our way past a dark blue lake and were crossing a great granite filled

bowl when I saw two men approaching, seemingly out of nowhere, from the

direction of Mount Russell. They were waving. I sensed it wasn't the llama mania

we'd been encountering . When they got closer I could see they were having a bad

time. They were wearing shorts and light shirts and had no packs. They looked

very cold. One had discolored lips. The taller of the two spoke with a heavy

German accent. "We are lost. Der way to Lone Pine, please." I tried to

explain they had to climb to Trail Crest (13,400 feet) and down the other side

to get to Lone Pine and their car. I knew I hadn't made myself clear when the

man went on. "We climbed Mount Muir (pointing to Mount Russell) and can't

find the way; 'twas cold in the night, no!"

I'd seen frozen water on the trail that morning and could imagine how

miserable their night had been. I gave them honey and motioned them to follow.

We came upon some backpackers who made hot chocolate and offered to escort the

unfortunate Germans over Trail Crest later in the day.

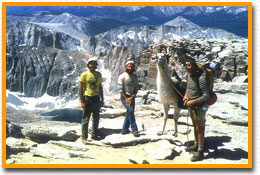

Sunny and I pushed on and came to a series of steep switchbacks that wove

through granite rubble and around great boulders. We came to a place where the

trail was erased by a slide. We had to pick our way through rough loose rock.

Here, probably more than anywhere else, Sunny showed the unique qualities of a

llama. If a rock was unsteady he withdrew his foot and groped until he found

stable footing. We reached Trail Crest without a stop and the sun was still low

in the sky. We pushed on towards the summit of Whitney. The ridge from Trail

Crest to the summit is spectacular. To the west is the entire southern Sierra

and beyond, and to the east is Death Valley and the Great American Desert. The

trail puts you directly on top of a sheer precipice that make you recoil for fear

of falling. You can see a lake 2,500 feet below off the east side that

appears to be directly beneath you.

Near the summit the trail disappeared into a snowfield. I let Sunny stand in

the snow for a few minutes then we headed for the top. I signed my faithful

companion into the book on the summit - "Name: Sunny Llama, Age: 3,

Address: Bonny Doon, California, Comments: Highest llama in North America - made

it no sweat."

I had been on top of Whitney before, but never was the view so clear. There

was no haze. When I went to memorialize the event I found my light meter wasn't

working. Dan Comelli, a total stranger, gave me readings from his meter which

resulted in some fine photographs. Whenever I maneuvered Sunny close to vertical

drop-offs, he'd back off the side and back at me with an expression that seemed

to say, "Why have you brought me here? There's no way down!" I had been on top of Whitney before, but never was the view so clear. There

was no haze. When I went to memorialize the event I found my light meter wasn't

working. Dan Comelli, a total stranger, gave me readings from his meter which

resulted in some fine photographs. Whenever I maneuvered Sunny close to vertical

drop-offs, he'd back off the side and back at me with an expression that seemed

to say, "Why have you brought me here? There's no way down!"

The descent back to Crabtree Meadow was hot and slow. I let Sunny take his

time for fear he would catch a foot in the endless cracks between rocks.

By the next evening we had backtracked over twenty miles, grabbed a few

minutes in the Hot Springs, and bedded down for a solid night's sleep.

Before sunrise I was up and in a couple hours we had climbed 2,500 feet out

of the Kern River Canyon and visited beautiful Sky Parlor Meadow. We saw about

twenty deer. We headed for Moraine Lake under ominous clouds that soon let loose

drenching rain. Draped in ponchos, we spent the afternoon sitting under a large Lodge

Pole Pine, watching lightning smash into nearby peaks. We set up camp

during a lull in the storm and spent the night in intermittent showers. By the

next morning the sky was gray in all directions. The storm appeared to be good

for two or three days. We were too low on food to sit it out so we decided to go

the last twenty-six miles, which included two climbs of 2,500 feet, all in one

day. We made Little Five Lakes averaging over two miles an hour. In drizzle and

with worsening skies we closed in on Black Rock Pass (11,200 feet). We raced

against the storm, hoping to get over the exposed summit before lightning

struck. Sunny followed closely, seeming to realize the urgency. We reached the summit

amid hail, slush, and thunder and started down the other side through a cloud.

Sunny looked half his normal size with his wet hair plastered to his wiry

body. The trail consisted of loose sharp rock. I was amazed Sunny's feet didn't

get cut or sore. After we'd descended to 6,800 feet we stopped, ate what we had

left, and started our last climb to Timber Gap. Sunny showed no signs of tiring.

He hadn't balked since the second day and seemed stronger than when we'd begun.

We traveled through some beautiful soaked forests and meadows and reached Timber

Gap at dusk. We continued in the dark and the rain. When car lights shown in the

valley far below, Sunny hummed anxiously. He knew the ordeal was ending. When we

finally reached the truck I gave Sunny a large flake of alfalfa, which he

gratefully attacked. I climbed into the truck cab and was quickly asleep. I

awoke twice during the night because of the pounding rain and peered out the

window at Sunny, who sat stoically behind the truck with the quiet resolve that

is purely llama.

|